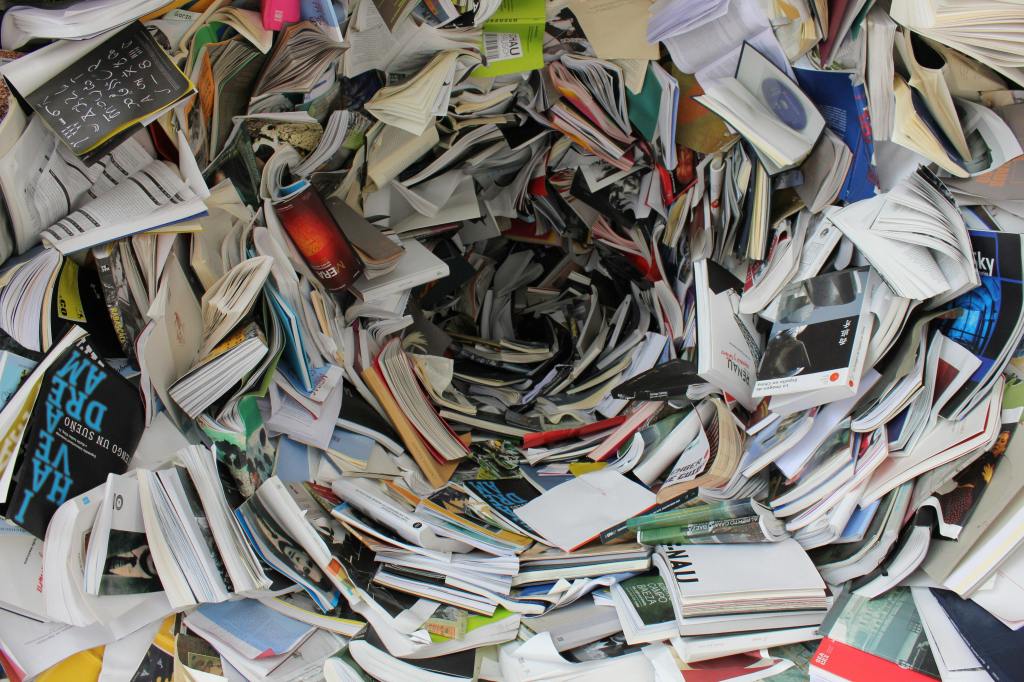

Our CPTSD programming not only makes us feel like sh*t— it often makes us feel incoherent.

We try to explain what we’re experiencing to others, friends, a therapist, whomever— but it just doesn’t come out right.

No matter the words we use, or how many words we use, we just…can’t…explain it the way it actually feels. The way it actually is.

Then…the shame sets in.

We don’t quite understand why we can’t express ourselves— but we know we feel embarrassed about it.

Turns out, that’s part of our trauma programming, too.

Trauma conditioning is real good at convincing us that EVERYTHING is our fault, and EVERYTHING is our responsibility.

At some point we just kind of give up trying.

Nobody is going to understand or care about our experience anyway— so we tell ourselves— so why bother?

You need to know: you are not as “incoherent” as Trauma Brain wants you to believe you are.

Remember that Trauma Brain not only wants you miserable, it also wants you silent.

CPTSD does NOT want you reaching out. It does NOT want you expressing yourself.

CPTSD wants you alone, hating yourself, convinced that no one can relate and no one cares.

So— it floods you with shame for even TRYING to express yourself.

It convinces you you can’t express yourself well.

It convinces you what you have to say doesn’t matter.

Listen to me: that’s bullsh*t.

You can express yourself.

What you have to say matters.

If I believed Trauma Brain’s bullsh*t, I wouldn’t be writing these words, and you wouldn’t be reading these words.

Keep trying to express yourself.

It’s true that not everyone will be able to keep up or appreciate your story or know how to respond— but that’s a them issue. Not a you issue.

You are not “incoherent.”

You are smart, you are articulate, and your words are key to your trauma recovery.

Breathe; blink; focus.