Very often we talk about the bummers of trauma recovery— and believe me, trauma recovery is full of profound bummers. Largely because trauma recovery is mostly about grieving losses.

But there is a sub-project involved in trauma recovery I really love: reclaiming art and entertainment that our trauma and abusers stole from us.

Very often trauma survivors lose, for a large chunk of our lives, art and entertainment that our nervous system associates with a traumatic experience or an abuser.

We can’t sand to hear the song that was playing on the car radio right before the crash.

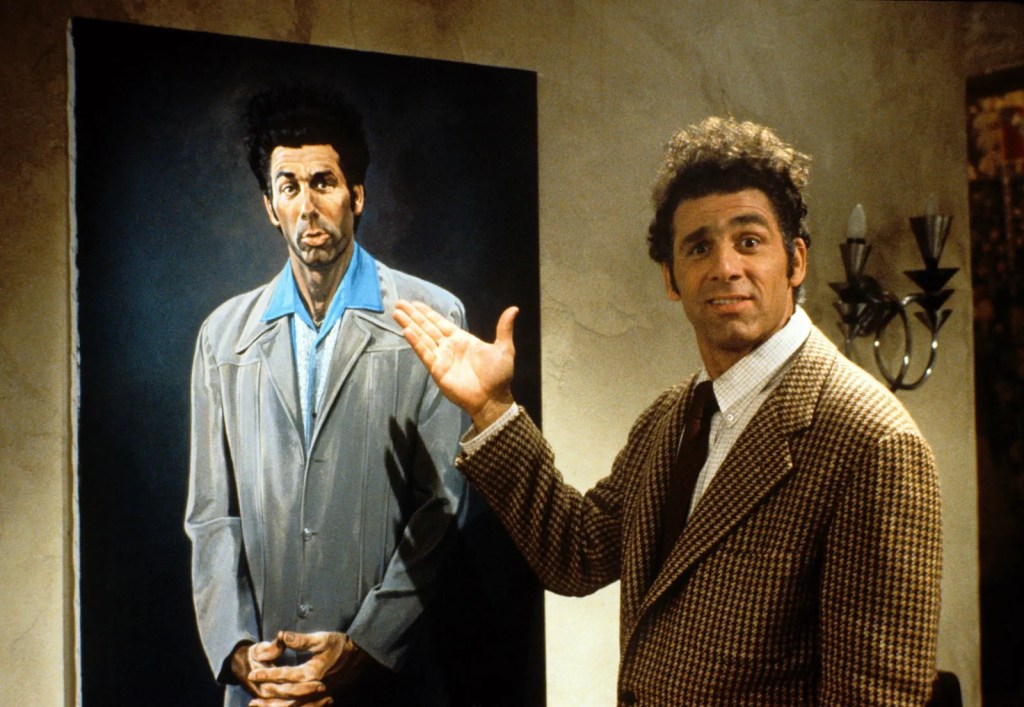

We can’t stand the TV show that our abuser liked and quoted.

We can’t stand the movie that we remember our abuser taking us to see.

We can’t stand the music an abuser wrote or performed.

It very often sucks, because, for as reactive as our nervous system can be to art and entertainment we associate with trauma or abuse, the art or entertainment itself is often kind of great.

It’s a dilemma many trauma survivors know all too well: we actually LIKE a piece of art or entertainment that our nervous system has become overwhelmingly reactive to, and we’ve thus had to limit our exposure to.

As we work our trauma recovery, we learn to disentangle art and entertainment from what happened to us or people who have hurt us— but it doesn’t happen by accident.

The reason why our nervous system is reactive to certain art and entertainment isn’t necessarily because of anything to do with the art or entertainment itself— it’s because of what we’ve been conditioned to believe that art or entertainment means.

Our nervous system has been conditioned to believe that hearing a certain song means that our abuser is near.

Our nervous system has been conditioned to believe that a certain TV show being on means that we might be back there, back then— and vulnerable.

Our nervous system has been conditioned to believe that playing certain music means we’re still in a relationship with an abuser.

Our nervous system has been conditioned to believe that a certain verse of a certain song means we’re about to crash— because we vividly remember not getting to hear the next verse of the song.

Changing our feelings about and reactions to art and entertainment we associate with trauma or abusers is all about changing the meanings we associate with it.

And the good news is: people change the meanings they associate with things all the time. Every day.

Have you ever changed how you felt about a political party or a religion?

Peoples’ political and religious beliefs tend to be entrenched, and people tend to be passionate about them— and yet, people change political parties and religions every day.

How does this happen? It happens when meanings change. A church that used to represent sanctity and safety now represents complicity and denial. A political party that once represented values we aligned with now represents corruption and deceit.

Many trauma survivors experience a shift in meaning when it comes to therapy or recovery: whereas therapy or recovery once represented “weakness” or “craziness,” now it represents strength and hope.

We can similarly change the meanings we associate with art and entertainment.

It starts with exposing ourselves to the art or entertainment in question— but in tiny increments, and with skills, tools, and support at the ready.

Sounds like a lot of work just to get to listen to a song, right? I suppose it is— but I think it’s worth it to reclaim our right to enjoy and find meaning in something.

Trauma and abuse rob us of many things— and some of those things, like our innocence or our childhood, may be lost forever.

Art and entertainment don’t have to be.

Trauma recovery asks us to do a lot of things that are hard, and the payoff to which isn’t immediately obvious.

Reclaiming our art and entertainment has a very observable upside.

Art and entertainment will never be not-important to humans— and detoxifying them, reclaiming them, can be an important milestone on our trauma recovery journey.